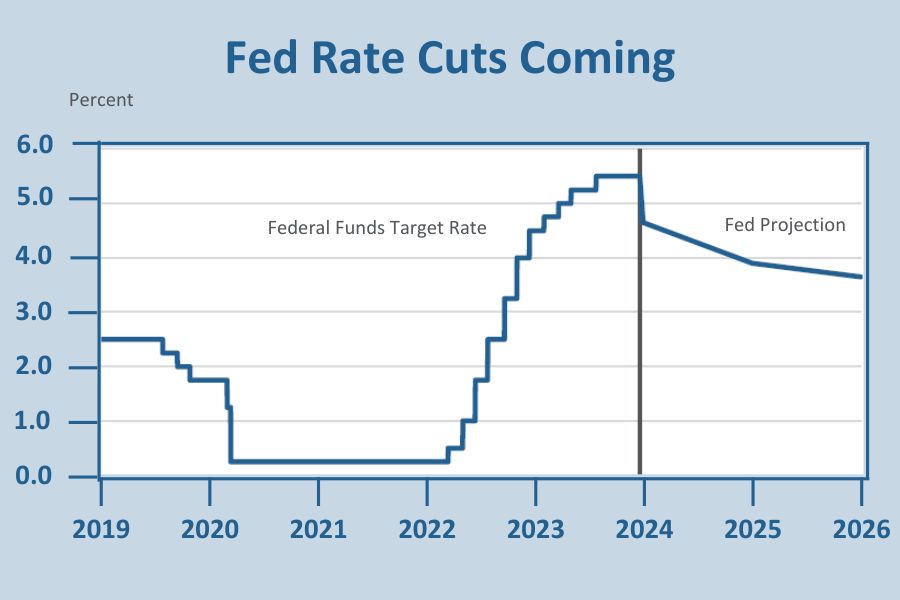

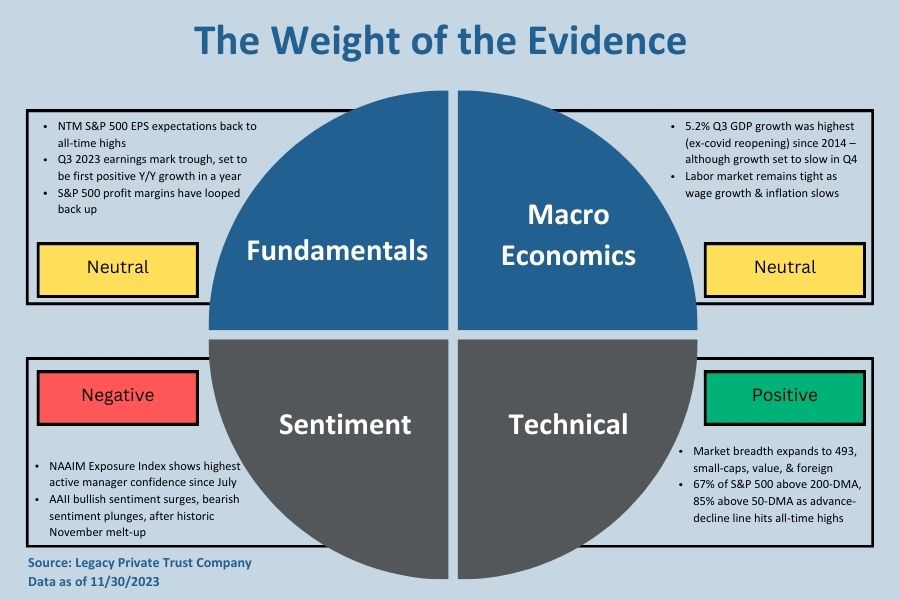

The era of low rates ended in March 2022 when the Federal Reserve started the most aggressive rate-hiking campaign in a generation, lifting their policy rate 11 times from near zero to a range of 5.25% – 5.50% in July of 2023, where it has remained. Until a few weeks ago, the central bank has wavered over what to do next: raise rates again or keep them “higher for longer.” The bias towards a more belt-tightening policy was understandable: Inflation remained far above the Fed’s 2% target, and, importantly, the rate hikes seemed to have little effect on the economy. Indeed, GDP accelerated to an eye-opening 4.9% growth rate in the third quarter, and unemployment has remained under 4% for 22 consecutive months – the longest stretch since the 1960s.

But as the calendar turns to 2024, the central bank is poised to switch gears. At their last policy meeting on December 13, they sent a strong message that the rate-hiking campaign has ended, and the next move will be down. The question is not one of direction but of timing. Fed officials projected three cuts during the next year, but not when the first one will occur. The financial markets are forecasting an even bolder pivot, pricing in six or seven cuts that would take the key policy rate – the federal funds rate – to below 4% by the end of 2024. Unsurprisingly, stocks and bonds staged big rallies following the latest Fed meeting.

It’s important to remember that Fed projections are just that —projections, not contracts that must be fulfilled or face legal penalties. Following the first hike in March of 2022, Fed officials predicted that the federal funds rate would wind up under 2% by the end of that year. It ended up at 4.5%. It’s also important to remember that financial markets tend to overreact to perceived policy changes, even nuanced ones, and suffer whiplash when perceptions by traders turn out to be wrong. Time will tell if history is about to repeat. From our lens, the good news is that the Fed appears to be on the right track after waiting too long to start the rate hiking cycle in 2022. Bucking almost every economist’s 2023 prediction, the so-called “soft landing” – a decline in inflation that doesn’t induce a recession – appears to still be within reach.

The Fed Pivots

It is not entirely clear why policymakers changed course at their December meeting, and it appears that not all are on board with the projected rate cuts. No single catalyst stands out. If anything, underlying conditions are more supportive of staying pat. Consumers, the economy’s main growth driver, are still spending at a healthy pace, the job market is still humming, and inflation, while retreating, is still above the Fed’s stated 2% target. A case can be made that the Fed is risking prematurely easing policy that could reignite the inflation embers.

But it would be a mistake for the Fed to wait until inflation gets closer to their 2% target before cutting rates. By then, it would be too late to cushion the economy from the damage that sustained high rates, not to mention the lagged effects of previous rate increases, would cause. You don’t want to wait until it starts raining to purchase an umbrella. By then, you will already be wet. A few months ago, the Fed believed that the risk of sustained high inflation outweighed the risk of a looming recession and a surge in unemployment. Hence, they decided to keep policy geared towards controlling inflation. Now, they perceive the risks to be roughly balanced.

Importantly, policymakers have repeatedly said they would start taking their feet off the brakes when inflation was sustainably trending towards 2%. Before hitting that target, there is still a way to go, but the trend is encouraging enough to believe it has staying power. Most inflation gauges have been running at annual rates of 3% or less over the last three and six months, and prices of many goods are outright declining, thanks to the healing of supply chain snarls that caused widespread product shortages during the pandemic. Many scoffed at the notion, held by the Fed in 2021, that the surge in those prices would be “transitory.” As it turns out, once supply caught up with demand, those prices have come down; it just took longer than expected to play out.

Growth and Inflation

Perhaps the most surprising part of the Fed’s pivot away from tightening is that the economy is running hotter than policymakers thought even a few months ago. At the September meeting, Fed officials expected GDP to increase by 2.1% in 2023, accompanied by a 3.3% inflation rate. They also predicted that one more rate increase would be needed to tame growth and prevent inflationary pressures from strengthening.

Three months later, at the December policy meeting, that combination of growth and inflation expectations was thrown in the garbage can, along with expected rate changes. In their fresh set of projections, the Fed members now expect GDP to grow by a stronger 2.6% in 2024, even as they lowered inflation expectations by 0.5% to 2.8%. The rate increase predicted three months ago has been taken off the table and replaced by the aforementioned three cuts predicted for next year.

Simply put, the Fed no longer sees growth as a driving force behind higher inflation, a striking about-face from the earlier sentiment held by many prominent economists – that only a sharp rise in unemployment and lower wages could tame inflation. Indeed, Chair Powell acknowledged at his post-meeting press conference that he was (pleasantly) surprised that inflation continued to retreat amidst an economy that continues to grow at a healthy pace. Not all are convinced this can continue, but some unfolding developments suggest it can.

The Last Mile May Not Be So Tough

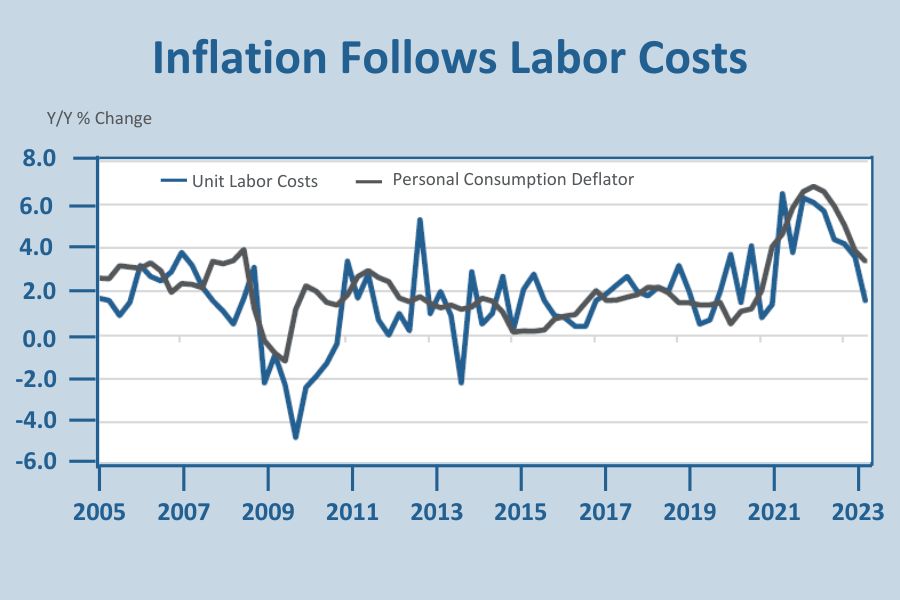

Despite the plunge in the inflation rate from a peak above 9% in 2022 to 3% today as measured by the overall consumer price index, there is a widespread sentiment that the easy pickings are over and squeezing the last 1% out of the CPI will be much harder. While prices of many goods are falling, prices of services are still running too hot; many believe that the inflation retreat will stall unless the underlying cause of service inflation, most notably labor costs, also comes down.

Undoubtedly, services prices are more closely linked to labor costs than goods, whose prices are influenced more by the cost of materials, transportation, exchange rates, and other non-labor factors. Restaurants, bars, medical practitioners, and barbers, among many other service providers, rely mostly on workers to generate revenues; hence, labor expenses have a major influence on how prices are set. While wage growth has softened over the past year, it is running above the pace consistent with a 2% inflation rate. Average hourly earnings are increasing by more than 4%, and median wages for a worker in the same job over the past year have increased by more than 5% from a year ago, according to the Atlanta Federal Reserve’s Wage Tracker.

But a key reason these increases are not fully passed on to consumers is that productivity has also increased by at least as much. Output per hour in the nonfarm sector surged by 5.2% in the third quarter, which offset the increase in worker compensation. Hence, the cost per unit of worker output declined during the period. Indeed, over the past year, unit labor costs increased by 1.6%, which is comparable to the pre-pandemic pace, and has declined for five consecutive quarters from 6.1% in the second quarter of 2022.

Wage Growth to Slow

Clearly, the productivity surge over the past year is not sustainable, as it reflects special post-pandemic influences, such as the rebound in output as supply chains healed. The AI revolution may also play a role, but that is likely to have more of a positive influence on stock prices than on output, although, in the longer term, its influence should increase. Past innovations, such as the widespread adoption of personal computers, took decades before they had the broad, diffuse productivity-enhancing impact that lifted output in every sector. And recent seemingly game-changing developments, such as the near-universal adoption of smartphones, have yet to have any discernable impact on positive or negative productivity.

It makes sense to measure true productivity trends over the course of a cycle. Stripping out the noise caused by the pandemic and its aftermath, productivity has increased by an annual rate of 1.5% since the fourth quarter of 2019, the same growth rate seen on average between the fourth quarter of 2007 and the fourth quarter of 2019. Assuming productivity growth is reverting to its longer-term trend of 1.5%, it would be necessary to slow nominal wage growth to around 3.5% to be consistent with the Fed’s 2% inflation target. Many believe that the labor market is too tight and worker bargaining power too strong for that to occur over the foreseeable future. The recent outsized gains by UPS and the United Auto Workers Union would seem to bear that out. However, workers bargained for those gains to catch up to past inflation, not expected inflation. One of the key successes of the Fed is that their aggressive rate hiking campaign kept inflationary expectations anchored. Recent surveys reveal that consumer inflation expectations are receding.

That said, worker bargaining power is tied to conditions in the job market. While unemployment is still historically low, that’s mainly because companies are not yet laying off workers. But overall, labor conditions are easing, as unfilled positions are declining, fewer workers are quitting, people are coming off the sidelines to join the workforce, and unemployed workers are taking longer to find a job, as reflected in a steady rise in continuing claims for unemployment benefits. This confluence of forces indicates that companies are cutting back hiring but are holding on to workers as they assess future staffing needs amid an expected slowing of economic activity. Workers are sensing this, and their wage demands are also easing as they see a loosening labor market. This unfolding scenario is looking ever more like a soft landing – a tapering off of wages and inflation without a recession-inducing spike in unemployment – which is precisely what the Fed aims for. The financial markets may be pricing more rate cuts than the Fed will deliver, but it seems policy is pivoting away from belt-tightening just in time.

If you are a Legacy client and have questions, please do not hesitate to contact your Legacy advisor. If you are not a Legacy client and are interested in learning more about our approach to personalized wealth management, please contact us at 920.967.5020 or connect@lptrust.com.

The information contained herein is for informational purposes only and does not constitute a recommendation or advice. Any opinions are those of Legacy Private Trust Company only and represent our current analysis and judgment and are subject to change. Actual results, performance, or events may differ based on changing circumstances. No statements contained herein constitute any type of guarantee, nor are they a substitute for professional legal, tax, or other specialized advice.