Has the Fed thrown in the towel? That’s the question investors are grappling with and those who think they know the answer are deceiving themselves. At the start of the year, the odds-on bet was that the central bank was poised to cut interest rates, a prospect that was fully embraced by the financial markets. The only questions were when the first cut would happen and how often the rate-cutting trigger would be pulled. The Fed had forecast three at their December policy meeting. That number was confirmed at the March confab when they also signaled that the launching date would come sooner rather than later. Traders were even more enthusiastic, pricing in as many as six rate cuts beginning early in March.

But, as the notable baseball philosopher Yogi Berra once said, making predictions is hard, especially about the future. While the Fed still believes that rate cuts are on the table, they are far less convinced than they were a month or two ago. A cavalcade of policymakers in recent weeks has sent a strong signal to investors not to expect the much-heralded move any time soon. Words by Fed officials have consequences in the financial markets, and the response has been as dramatic as it was predictable. Just as the signal of rate cuts stoked a sharp stock market rally in the first quarter, the hawkish pivot in April sent prices skidding. It also drove market interest rates sharply higher, lifting mortgage rates above 7%, except for a brief period last October, which is the highest since 2007. That should make home buying even less affordable for a broader range of the population, amplifying the struggles of the beleaguered housing market.

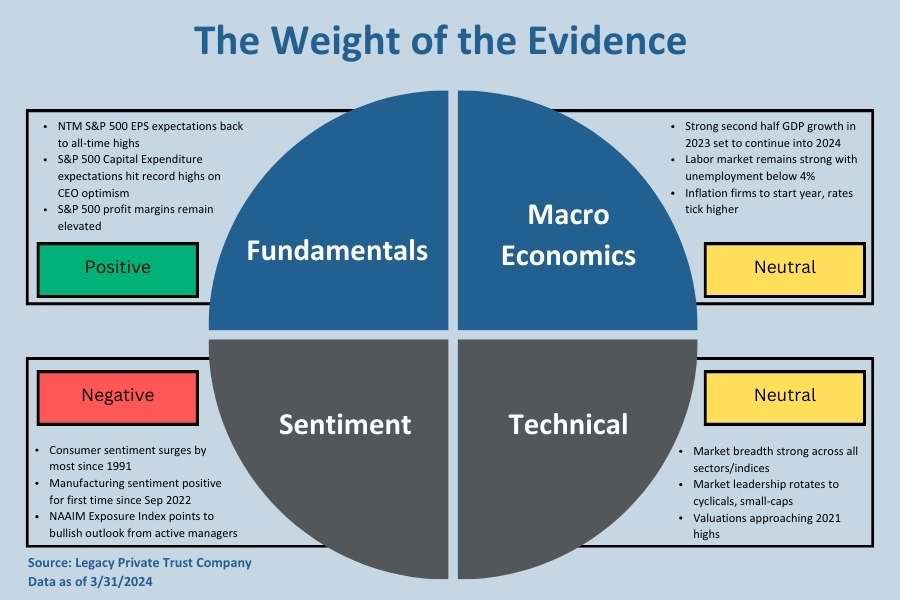

What changed to upend an economic and financial landscape that seemed so bright a few months ago? At first blush, not much. The economy is still chugging along, unemployment is hovering near historic lows, and consumers, who seemed to stumble early in the year, reopened their wallets in March, indicating that the economy’s main growth driver has recaptured its spending mojo. But while investors and policymakers, not to mention the public, were happy with the economy’s strength last year, they are less so now. That’s because, unlike in 2023, the economy’s muscular performance is not occurring alongside slowing inflation. Instead, consumer prices have turned hotter from month to month during the first quarter, threatening to undermine the Goldilocks scenario that had been unfolding and prompting the Fed to keep rates higher for longer. High inflation and interest rates are not a recipe for good cheer on Wall Street or Main Street. Will this combination end in a veil of tears?

Slowing Inflation Trend Stalls

Weather and inflation have something in common: everyone complains about them. But while nobody does anything about the weather, as noted by Mark Twain, inflation does have a whipping stick at the ready when it gets out of hand. The holder of that stick is the Fed, which clearly moved aggressively to tame an unruly price uprising by cranking the federal funds rates up by 5.25 basis points since March 2022. That tough response tamed the inflation dragon, slowing price increases from over 9% to 3% over the second half of last year. It was widely believed that this trend would continue and soon land at the Fed’s 2% target, setting in motion the rate-cutting expectation that delivered strong gains in the financial markets during the first quarter.

However, progress on inflation stalled this year, as did the optimism that permeated investors’ mindsets. After hitting 3.1% last November, the retreat in the annual increase in the consumer price index has hit a wall. Worse, the monthly increases have turned hotter. Some of the reversal can be blamed on rising oil prices, stoked by geopolitical factors. However, the pattern is the same when price measures are stripped of volatile energy and food prices. Nor has the Fed’s preferred inflation gauge, the broader personal consumption deflator that is made available several weeks after the consumer price Index comes out, shown any progress since the start of the year.

One reason for the stickiness of inflation is high housing costs, which carries an outsized weight in the price indexes. However, the data on housing is skewed by rent increases that occurred at least six months ago. Rent is increasing much more slowly now and is declining in many regions. Recently, the Fed has been closely monitoring service prices, excluding housing. Unfortunately, the recent trend in that so-called supercore index has been even hotter than the overall consumer price index, and this may be one reason the Fed has become more adamant about keeping rates higher for longer.

Waiting For Cooling Job Market

The Fed’s focus on super-core inflation reflects the fact that these service prices are linked to wages, which are the largest expense items for most of corporate America. While wage growth is slowing, it is not doing so as rapidly as the Fed would like. According to most measures, labor cost increases run about 1.5% above the threshold, which is consistent with 2% inflation. That threshold is not set in stone, as stronger productivity growth allows wages to rise faster without boosting inflation. Indeed, that’s clearly what happened in the second half of 2023, when inflation retreated despite above-trend wage growth.

However, last year’s 2.6% productivity surge is not sustainable and should revert to its trend of 1.5% annual pace. The Fed would like to see wage growth slow to around 3.5% before they feel comfortable that inflation is moving sustainably toward its 2% target. For that to happen, the job market needs to cool from the torrid pace seen last year. With job growth accelerating in the first quarter, that clearly has not happened yet. There are still 1.4 open positions for every unemployed worker, and the unemployment rate has hovered under 4% for the longest period since the 1960s.

With the supply of labor not expected to grow as strongly as last year, the Fed is laser-focused on slowing the demand for workers. The hope is that companies will reduce hiring rather than spurring rounds of massive layoffs, which would lead the economy into a recession. The April jobs report was not available at this writing, but the economy generated far more payrolls in the first quarter than anyone expected, including the Fed. Given this backdrop, it is unsurprising that wage growth is not slowing more rapidly or that the Fed is delaying rate cuts.

Longer Lags

It is an accepted maxim in economic circles that monetary policy affects the economy with long and variable lags. Following the largest and fastest rate hike cycle since the 1970’s, most economists believed the economy was heading for a recession last year. But expectations of a “hard landing” softened as it became apparent that the economy was holding up. By late in the year, the consensus view was that the economy was instead heading for a “soft landing,” i.e., below-trend – but nonrecessionary – growth accompanied by slowing inflation. This condition would allow the Fed to cut rates to keep the expansion going. The narrative has shifted to a “no landing” scenario accompanied by sticky inflation that may prevent the Fed from easing policy.

So why hasn’t the economy buckled under the highest rates in over two decades? That’s the trillion-dollar question. It has been over two years since the Fed started to hike interest rates, which is longer than usual for a tightening cycle not to bring about economic stress. During this time span, some historically reliable yardsticks, including the Conference Board’s leading economic indicators and an inverted yield curve, sent out strong signals that a recession was on the way. But here we are, still chugging along with no end in sight to the expansion.

We hesitate to say that this time is different because it rarely is. But we can confidently say that every cycle is different, and this one is unique in many respects. Coming off a decade of nearly zero interest rates, households and corporations had ample opportunity to lock in low rates on their debt obligations, a good chunk of which is still outstanding. For them, the rate hikes over the past two years have had little or no effect on their debt-servicing charges. Most homeowners, for example, are sitting on mortgages with rates that are 3-4 percentage points below the current 7.1%. Likewise, corporations locked in low rates issued long-duration bonds in the capital markets, and can also take advantage of 5%+ yields on their burgeoning cash balances.

A Blessing and a Curse

Therefore, It is no surprise that private interest payments have barely risen over the past year. But that sweet spot for many borrowers is about to end. A growing swath of business debt incurred during the early stage of the decade-long low interest rate period is coming due and will need to be refinanced at the current higher rates. This is particularly concerning for the debt-laden commercial real estate sector, where vacancies are historically high as remote work has proliferated.

Those locked-in low rates among households are both a blessing and a curse. They insulate homeowners from rising mortgage rates but keep those who want to sell their homes locked in because they do not want to give up their low-rate mortgages. This strips the housing market of inventory and drives home prices higher. The high current level of mortgage rates and ever-higher home prices are shutting millions of new home buyers out of the market. Meanwhile, unlike mortgages, debt repayments on credit cards and auto loans are spiking as these forms of short-term borrowing are immediately impacted by the Fed’s rate hikes. Not only are these hikes taking a toll on lower- and middle-income consumers – leading to rising delinquencies – but small businesses also rely heavily on revolving credit lines to fund operations. Remember that small firms are the biggest generator of jobs, and restrictive credit conditions are already prompting them to scale back hiring plans.

Simply put, the lagged effects of the Fed’s rate hikes are starting to kick in even as pandemic-era savings are being depleted, erasing a key source of household purchasing power. This points to weaker demand in the coming months, which will undercut business pricing power and support a resumption of slower inflation. It is taking longer for monetary policy to transmit its effects through the economy, thanks largely to the unique environment that preceded the rate-hiking cycle. The Fed must be careful not to keep their foot on the brakes too long based on backward-looking conditions that make it take longer to respond to its efforts. Odds are, they will see enough progress on the inflation front and slower growth to start cutting rates later this year.

If you are a Legacy client and have questions, please do not hesitate to contact your Legacy advisor. If you are not a Legacy client and are interested in learning more about our approach to personalized wealth management, please contact us at 920.967.5020 or connect@lptrust.com.

The information contained herein is for informational purposes only and does not constitute a recommendation or advice. Any opinions are those of Legacy Private Trust Company only and represent our current analysis and judgment and are subject to change. Actual results, performance, or events may differ based on changing circumstances. No statements contained herein constitute any type of guarantee, nor are they a substitute for professional legal, tax, or other specialized advice.