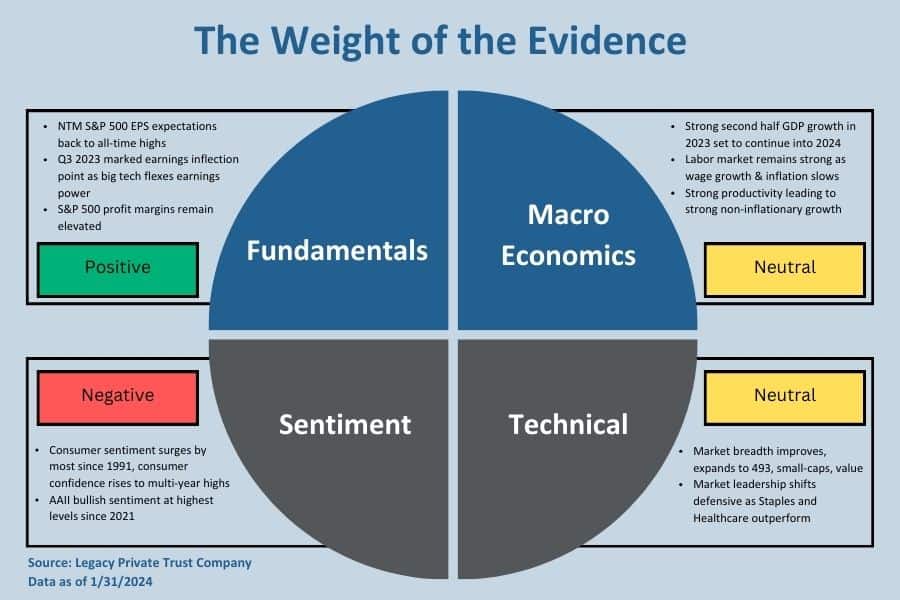

January tends to be an ornery month for economists, and the calendar did not disappoint this year. In the closing months of 2023, a Goldilocks economy appeared to be unfolding. It featured a cooling but still solid pace of economic activity amid a steady decline in inflation. Against this backdrop, investors had fully priced in expectations of a Federal Reserve rate cut as early as March; stock prices rallied strongly, and bond yields plunged. But as the notable baseball philosopher Yogi Berra famously said, “The game ain’t over till it’s over.” As the curtain rose on 2024, things appeared to be going off the rails. Instead of cooling, some key economic indicators, most notably job growth, came in hotter than expected in January, and more disconcertingly, inflation picked up.

To their credit, the Fed never capitulated to the growing rate-cutting pressure late last year. Despite the significant cooling of price pressures over the year’s second half, they were not convinced that inflation was firmly on the path to their 2% target. Wages were still growing too rapidly, service price increases remained elevated, and the economy and the job market continued to chug along in the face of more than 500 basis points of interest rate increases since early 2022. Still, the Fed pivoted away from their rate-hiking campaign, projecting rate cuts in 2024—just not as early or steep as traders expected.

For a while, the markets and the Fed were at odds as investors entered 2024, still expecting the central bank to cut rates early in the year. However, January’s employment and consumer price reports quickly put the kibosh on that notion. As the March policy meeting approaches, no one expects a move as investors are now fully aligned with the Fed’s ongoing intention to keep rates “higher for longer.” The earliest rate cut that is currently priced into the markets is June. If incoming reports echo the strength in jobs and inflation shown in January, the first reduction could be delayed to later in the summer. The direction inflation takes in the coming months not only impacts monetary policy and interest rates but it could also influence the presidential election in November.

Inflation and the Elections

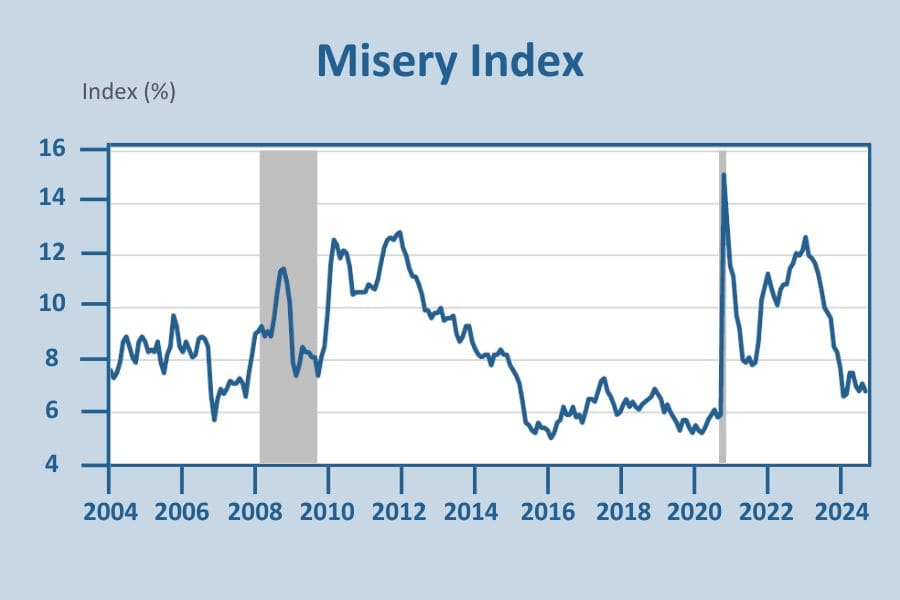

The presidential election is rapidly approaching, and the post-pandemic bout of alarmingly high inflation has pushed this issue to the top of people’s concerns. How voters perceive inflation, among other economic developments, will influence the outcome of what appears likely to be a rematch between incumbent President Joe Biden and former President Donald Trump. Subjective matters influence voter decisions, but they are impossible to build into economic models that rely on objective data to generate projections. However, polls show that Americans care deeply about inflation, and there are three scenarios that voters in key battleground states may bring with them to the ballot box on election day.

The first scenario – aptly known as the sticker-shock situation – is one in which voters fixate on the cumulative increase in consumer prices since Inauguration Day. This is the scenario that grabs headlines, as it is the one that people complain loudly about. Their anger is directed particularly towards frequently purchased items – such as groceries and gasoline – that cost 20% more than on Biden’s inauguration day. Unsurprisingly, this is the model that produces the most unfavorable result for the incumbent president.

While households typically focus on the level of prices – especially on necessities like food and energy – economists prefer to look at the year-over-year percentage change in consumer prices. The second scenario assumes swing voters think more like economists and reward the incumbent president for the moderation in inflation. Inflation has fallen dramatically since hitting a peak in the fall of 2022. Even with the January surprise acceleration, the annual increase in the consumer price index has plunged to 3.1% from its 9.1% peak. What’s more, prices of many products are falling, particularly big-ticket items like automobiles; indeed, prices of all goods, excluding food and energy, are lower than they were a year ago for the first time since the post-pandemic inflation cycle got underway in 2022.

The January Effect

It is a time-honored adage in economics that one month does not make a trend. While that is true for any month, it is particularly the case in January. It’s important to remember that this month follows some key holidays, including Christmas, Hanukkah, and Thanksgiving. Companies ramp up seasonal hiring, leading to those events to accommodate an anticipated sales rush. Conversely, when those holidays are over, and sales revert to normal patterns, companies lay off those workers.

The government statisticians recognize seasonal hiring quirks and adjust incoming data so that their seasonality is removed, and apples are compared to apples when gauging changes from month to month. However, the seasonal adjustments also change from year to year to account for evolving trends, and it appears that they have become less reliable in the post-pandemic environment, which has upended traditional spending and hiring patterns. With labor costs accelerating amid a tight labor market, companies likely hired fewer seasonal workers leading up to the holidays and, hence, had fewer layoffs than normal in January. Since the seasonal adjustment factors assume larger layoffs, they yielded a surprisingly strong seasonally adjusted increase in jobs in January that probably temporarily overstated the strength of the job market.

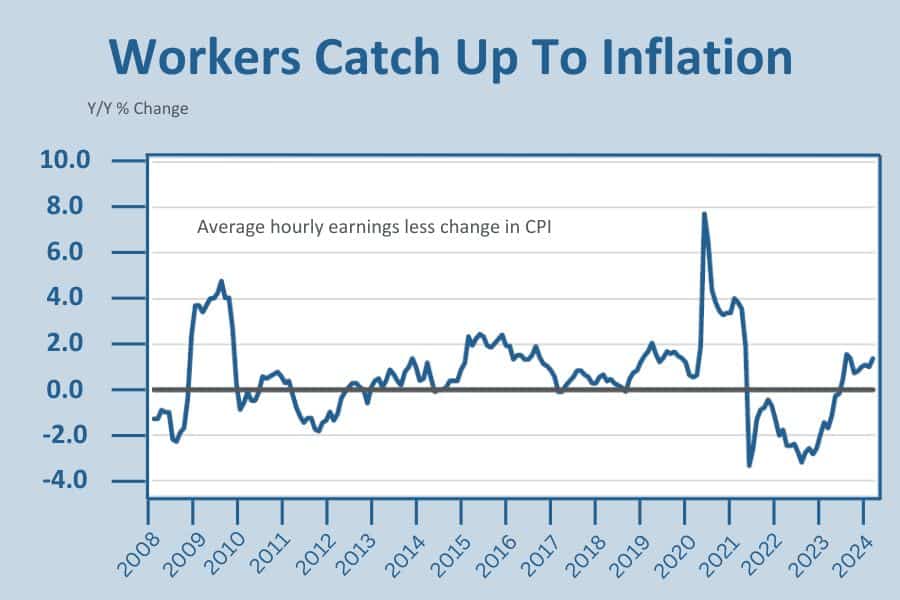

A similar story may apply to the surprisingly hot monthly consumer price report. In January, businesses tend to reset prices to recover the higher costs incurred over the previous year. Not only did worker earnings stage a robust advance last year – well above the pre-pandemic trend – but it was also the first time since 2020 that average hourly earnings increased faster than consumer prices. Recall that some major union contracts that generated hefty pay raises were negotiated during the year. Importantly, service sector employees received the biggest wage increases, as labor shortages were particularly severe for restaurants, hospitality, and healthcare workers. This is significant because labor costs have a much bigger influence on prices in the services sector than in the goods-producing sectors.

Bumpy Road

We suspect that the larger-than-expected increase in the consumer price index in January was influenced by these one-off factors, just as the payroll surge reflected fewer layoffs than normal rather than a burst of hiring. Both inflation and job growth should revert to a cooling trend in the coming months. That said, the hotter-than-expected data during the month was a wake-up call for rate-cutting advocates who believed that the inflation retreat was on a one-way path towards 2%, encouraging the Fed to cut rates sooner rather than later. The economy rarely moves linearly, as potholes are more likely than not to cause mid-course corrections. The challenge for policymakers is to recognize the bumps in the road and remain focused on the broader picture.

Odds are, just as the Fed held firm while inflation receded late last year, they are not likely to let a one-month flareup in consumer prices and job growth sway them from their intention to lower rates later this year. That plan – to cut rates by about three-quarters of a percent – was presented in the economic projections at the December policy meeting, when the prospect for a soft landing loomed large. The financial markets took that prospect and ran with it, with the S&P 500 up over 20% since late October. The wake-up call in the January data brought investors back to their senses. That said, this is no time for complacency, and the Fed needs to stay nimble in its approach to policy in the coming months.

Keep in mind that the economy has landed in a good place – still chugging along even as inflation is receding – due to a combination of flexible policy decisions as well as good luck. When the Fed realized they had waited too long to start pushing back on inflation – believing it was due to a transitory shock – they abruptly changed course and aggressively slammed on the brakes starting in the spring of 2022. That delayed response led to a long catch-up phase, generating the steepest rate-hiking cycle in over forty years. Importantly, they stayed the course until pausing in July of last year despite mounting calls that the economy would suffer a hard landing.

Good Luck

The fact that the economy remained so resilient has as much to do with luck as with policy decisions. The Fed was prepared to accept a mild recession to conquer the inflation dragon and was just as surprised by the economy’s muscular performance late last year as everyone else. They underestimated the firepower the huge pandemic-era savings buildup had in stoking the economy’s growth. They also underestimated the supply of workers that would return to the labor force, allowing wage growth to cool amid a hot job market.

However, banking on more good luck is not a strategy; the Fed’s decision to keep rates higher for longer — reaffirmed at the late January policy meeting— heightens the risk that a hard landing will be the price paid for overstaying the inflation fight. The hotter-than-expected January data validates the Fed’s current decision to keep rates elevated. Still, they also signaled that they are more concerned about cutting rates prematurely before inflation is decisively under control rather than waiting too long and risking a recession. That preference is a bit odd, as there is a lot of further disinflation in the pipeline, particularly for goods, and the wage hikes last year that are putting pressure on service prices are in the rear-view mirror. If the central bank waits for clear signs that the job market and the broader economy are deteriorating, they will be behind the curve, much as they were behind the inflation curve in the spring of 2022. In that case, it will require more luck to avoid a recession.

If you are a Legacy client and have questions, please do not hesitate to contact your Legacy advisor. If you are not a Legacy client and are interested in learning more about our approach to personalized wealth management, please contact us at 920.967.5020 or connect@lptrust.com.

The information contained herein is for informational purposes only and does not constitute a recommendation or advice. Any opinions are those of Legacy Private Trust Company only and represent our current analysis and judgment and are subject to change. Actual results, performance, or events may differ based on changing circumstances. No statements contained herein constitute any type of guarantee, nor are they a substitute for professional legal, tax, or other specialized advice.