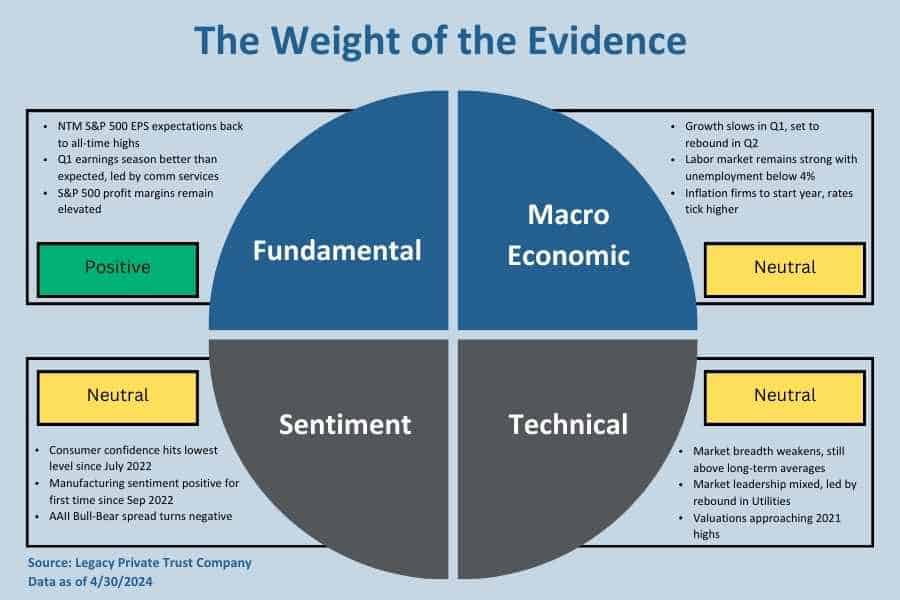

For economists and policymakers, waiting for inflation to subside is like waiting for Godot. But that time may finally have arrived, as the consumer price index rose less than expected in April while the less-volatile “core” consumer price index dropped to the lowest level since April 2021. It was the first time this year that inflation did not surprise on the upside, giving hope that the extensive efforts by the Federal Reserve over the past two years are finally bringing results. One month does not represent a trend, and the tame inflation reading in April will not prompt the central bank to start unwinding the steep interest rate hikes it implemented from March 2022 to July of last year. But it stifles concern that more rate hikes might be needed to finish the job.

Unsurprisingly, the good news on the inflation front stoked a joyous response in the financial markets. Stocks raced to new highs shortly after the CPI report was released on May 16, and market yields erased some of the runup that occurred before the release. If those trends stick, the beleaguered housing market will benefit from lower mortgage rates, and low and middle-income borrowers will gain some relief from lower debt servicing charges on credit cards and auto loans. But markets are fickle, and if the next wave of data reveals that the April inflation report was a fluke, the celebration will fizzle quickly. Simply put, patience is needed to gain a more conclusive understanding of unfolding events.

That said, there are reasons to be cautiously optimistic that the steep inflation retreat last year will resume after being rudely interrupted over the first three months of this year. For one, some temporary forces that boosted inflation early this year are already fading. For another, consumers are not as accepting of higher prices as they were earlier in the inflation cycle when they were flush with enormous government stimulus payments that bloated bank accounts. Finally, inflation is fueled by imbalances between demand and supply in the product and labor markets. Both are getting into better balance, and the rebalancing should continue. It’s taking longer than most expected, but the conditions for sustained lower inflation are falling into place, setting the stage for belated rate cuts before the end of the year.

The Disconnect

Over the past three years, pundits have been scratching their heads over a headline-grabbing disconnect regarding the economy’s health. Over that period, almost 15 million jobs have been created, unemployment has remained under 4% for 27 straight months, the longest stretch since the 1960s, wage gains have outpaced inflation, and household net worth has surged to all-time highs, juiced by a strong stock market and rising home values. Yet, survey after survey reveals that the public is in a dismal mood, feeling as downbeat about economic conditions as during previous recessions and convinced that the economy is heading in the wrong direction.

A disconnect between perception and reality is not unusual and is often downplayed by economists because people do not always behave as they feel. However, the unusually wide gulf this time is hard to explain. Many commentators chalk it up to politics, noting the highly polarized state of the U.S. electorate. No doubt that is having an influence, as these same polls reveal vastly different sentiment readings among Democrats and Republicans, with the former viewing conditions through a much brighter lens than the latter. That said, pocketbook issues dominate how people feel regardless of party affiliation, and the one negative impulse that affects everyone is inflation. People feel bad when things cost more, particularly if prices increase faster than wages.

That, in turn, may be the overarching anchor that is sinking the mood of households. To be sure, measuring inflation against worker earnings is not a clear-cut exercise. It depends on the time frame you are evaluating. If you go back to the pandemic’s start in early 2020, worker earnings have kept pace – and even exceeded by a tad – inflation. But a more representative period to measure public angst should begin when inflation started to take off in the spring of 2021. Over these three-plus years, average hourly earnings grew by 15.6%, but consumer prices have risen by 18.2%. Hence, despite sturdy gains in workers’ pay, they have still not caught up with the price rise. Average hourly earnings adjusted for inflation for all workers fell to $11.02 this April from $11.35 in March 2021.

Level Versus Change

The decline in real earnings explains why the hot job market and solid nominal wage increases have not prevented spirits from sinking, even though inflation has retreated from a peak of 9.1% in mid-2022 to 3.4% currently. Price increases are slowing, but the cost of goods and services is still taking a bigger bite out of budgets than was the case three years ago. What’s more, lower-income households have suffered the most significant decline in purchasing power because they spend more on essentials – food, gasoline, and rent – whose prices have gone up faster than the average of all prices. Groceries, for example, cost 21% more than three years ago, and gasoline 40% more.

The good news for low and middle-income households is that price increases for essentials are leading the way lower. Grocery prices have been falling for the past three months and are virtually unchanged from a year ago. Gasoline prices are declining even faster and are 15% below what they were last September. The one big exception in this group of essentials is rents, which continues to be a key influence lifting the consumer price index. However, the CPI, including all rents over the past year, does not fully reflect the slower increases occurring on new leases.

These declines are a sure-fire signal that consumers are becoming less tolerant of higher prices than they were earlier in the inflation cycle when the government’s pandemic relief programs supplemented their purchasing power. Those programs have mostly ended, and the cash cushions they provided are mostly depleted. Significantly, major retailers recognize the squeeze on budgets that a broadening swath of their customers are experiencing. Recently, several large chains and big box stores, including Target, announced they are slashing prices on groceries and thousands of other essential goods that will extend through the summer months.

Long Memories

When will the public recognize and applaud the slower price increases over the past year? That, in turn, brings up another disconnect that bedevils the White House and policymakers. People have long memories; they remember what prices were three years ago and are more chagrined over the nearly 20% more they are paying for goods and services than the fact that those prices are increasing at a much slower pace. No doubt, if income growth had outpaced inflation over the past three years, people would be less upset over the higher prices. But if incomes had increased faster, demand and inflation would have increased, prompting the Fed to hike interest rates even higher. That, in turn, would have made the prospect of a hard landing for the economy more likely.

It’s unclear when the current slowdown in price increases will outweigh the higher level of prices relative to three years ago in households’ minds. The timing, however, is essential because the longer consumers fret over high prices, the greater the odds they will reduce spending, particularly if anxiety over job security increases. That prospect, moreover, would become likelier if the Fed continues to prioritize reaching their 2% inflation target over avoiding a recession by keeping rates high for too long.

The best-case scenario would be that the relationship between wage growth and prices seen over the past three years flips. Instead of an unequal rise wherein inflation outpaces wage growth, the Fed wants to see an unequal decline, wherein inflation slows more than wage growth. That would leave workers with more purchasing power and allow the Fed to start cutting rates, staving off any possible recession. This describes the heralded soft landing that the financial markets are pining for and the Central Bank hopes to achieve.

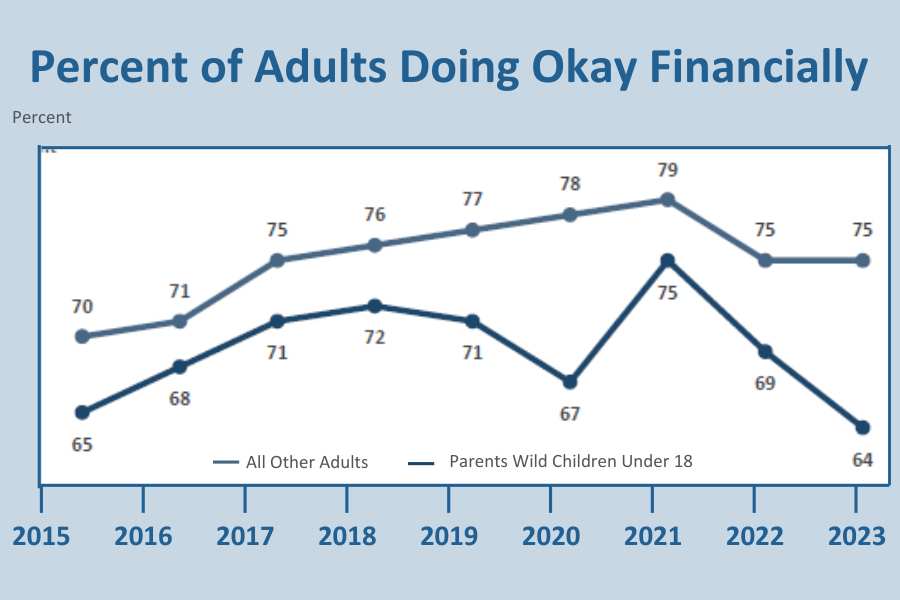

Parents Feeling More Pain

Granted, there is no rush to cut rates, as the economy is still strong despite the public’s grim perception of conditions. The economy’s growth engine did downshift in the first quarter, thanks mainly to a pullback in inventories and a wider trade deficit. However, the slowdown in GDP growth to 1.6% from 4.2% over the second half of 2023 masked more robust consumer spending and business investment. Still, the first quarter’s performance was marred by an upturn in inflation that put the markets and the Federal Reserve on edge.

From our lens, a major risk is that the Federal Reserve will be overly influenced by the backward-looking inflation data that, as noted earlier, were skewed by some unusual forces. Notably, a surge in insurance costs – on autos, healthcare, and homes – gave inflation a big boost early in the year. However, these increases reflect a one-time resetting of prices to cover substantial cost increases that occurred in 2023. For example, car prices and the cost of auto repair jumped last year, prompting insurers to pass on those costs to customers in the form of higher insurance prices. But that inflation boost is already fizzling, as auto prices have declined every month so far this year.

One cost that continues to squeeze households – and threatens to undercut spending – is childcare expenses. According to a recent Federal Reserve survey, a much higher percentage of parents of children under 18 suffered a significant decline in their financial well-being last year. In contrast, the percentage of all other adults who felt they were financially OK was virtually unchanged from the previous year. Childcare is one major cost item that is not likely to decline in the near future, given the shortage of workers in this sector, which is driving up labor costs. This is also one area where perception and reality converge and add to the financial burden that is weighing ever more heavily on low- and mid-income households. However, childcare costs may become more of a burden on upper-income households as well, particularly if the job market softens and closes the door for parents to work remotely from home. In that case, the downbeat mood of households would become more of a threat to the broader economy as people are more likely to behave as they feel. Either way, the Fed has little control over childcare costs and should start cutting rates before they risk dragging the economy into a recession.

If you are a Legacy client and have questions, please do not hesitate to contact your Legacy advisor. If you are not a Legacy client and are interested in learning more about our approach to personalized wealth management, please contact us at 920.967.5020 or connect@lptrust.com.

The information contained herein is for informational purposes only and does not constitute a recommendation or advice. Any opinions are those of Legacy Private Trust Company only and represent our current analysis and judgment and are subject to change. Actual results, performance, or events may differ based on changing circumstances. No statements contained herein constitute any type of guarantee, nor are they a substitute for professional legal, tax, or other specialized advice.