As expected, the Federal Reserve held rates steady at the September 19-20 policy meeting, following 11 hikes over the last 18 months that lifted short-term rates from near zero to a range of 5.25% – 5.50%. The jury is still unsure whether the central bank has reached the end of the rate-hiking cycle aimed at wrestling inflation down to its 2% target, a level that prevailed over most of the 20 years before the post-pandemic inflation surge. As hard as it is to remember, a major concern during that pre-pandemic period was the difficulty of getting inflation up to at least 2%, an effort that, not coincidentally, underpinned the low-interest rate environment that had prevailed since the 2008 financial crisis.

Just as the tame inflation and low interest rate environment of the pre-pandemic years seems like a distant memory, the last two years of elevated inflation and high interest rates are seen by many as a permanent feature of the U.S. economy. That would be a mistake. It’s highly unlikely that we will see “free money” again any time soon, as it would take a lot of economic pain and strong deflationary forces for the central bank to drive interest rates down to zero again. But evolving trends strongly indicate that the Federal Reserve is near, if not at the end of, hiking rates, and the economy is near, if not at a tipping point that will lead to a slowdown from the 10% nominal GDP growth over the last few years.

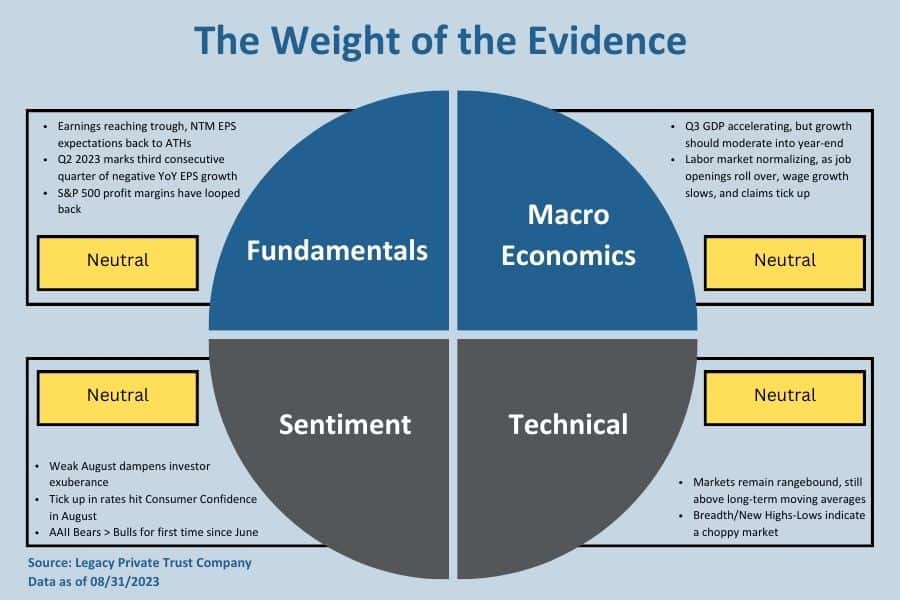

Granted, on paper the economy headed into the fourth quarter looking far more robust than expected a few months ago. Earlier in the year, most economists and traders believed the U.S. would be sliding into a recession by now and the Fed would be cutting rates. The consensus view was that the combination of the rapid rate hikes since early 2022 and high inflation would be too much for the economy to bear, prompting consumers to pull in their horns and businesses to lay off workers. When several large regional banks failed in the spring, creating a mini financial panic, recession fears surged, cementing that doomsday conviction. But businesses and consumers hardly blinked, as the former kept expanding payrolls and the latter kept spending. Instead of slowing, data for the just concluded third quarter is tracking a 4-5% growth rate, which would be even stronger than the 2% growth observed over the year’s first half. But that tracking rate is misleading, as it is all front-loaded into July when households were still flush with pandemic savings and prices were rising faster than costs, boosting corporate profits. Since then, activity has downshifted, and the economy is facing a rough patch in the year’s final months. A soft landing is still possible – and has gained many adherents in recent months — but is certainly not a foregone conclusion.

Why Rate Hikes Didn’t Do More Damage

Despite the downbeat sentiment early this year, the economy powered through the insurmountable hurdles, most notably the rapid climb in interest rates, high inflation, and the financial turmoil following the bank failures in the spring. Forecasters were hard-pressed to explain why these headwinds failed to have more of a growth-retarding impact than they had. In hindsight, some of the reasons now seem obvious.

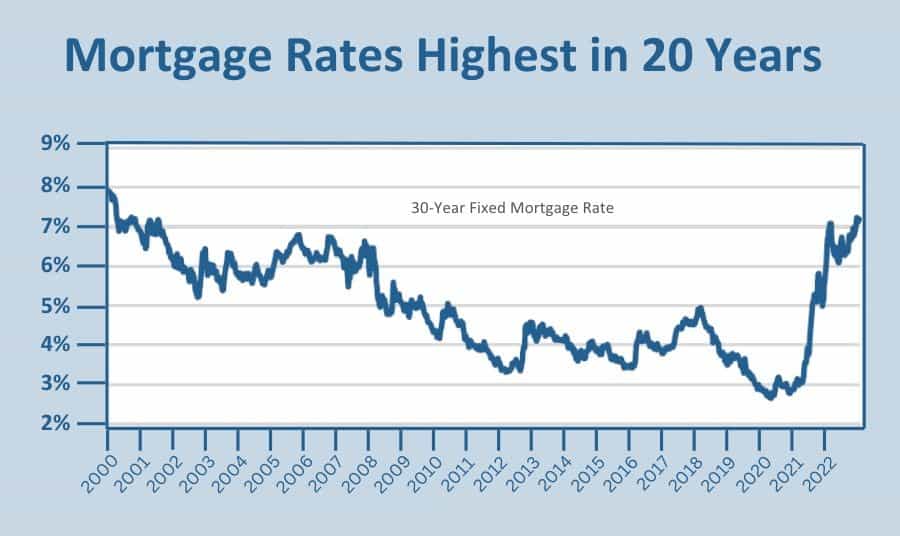

Take, for example, the failure of sky-high interest rates to deter consumer spending, which was the biggest growth driver over the year’s first half. Higher borrowing costs didn’t stifle purchases because households retained a bulwark of formidable spending power — the $2.1 trillion of excess savings built up during the pandemic. Hence, even as job growth and wage gains slowed over the first half of this year, households tapped into this cushion of savings to sustain spending. Those drawdowns more than compensated for the slowdown in income growth this year. Consumer’s largest borrowing costs – their mortgages – have also remained low, thanks to the locked-in mortgages taken out in 2020 and 2021. The average mortgage rate on a home in the U.S. sits at just 3.6% today.

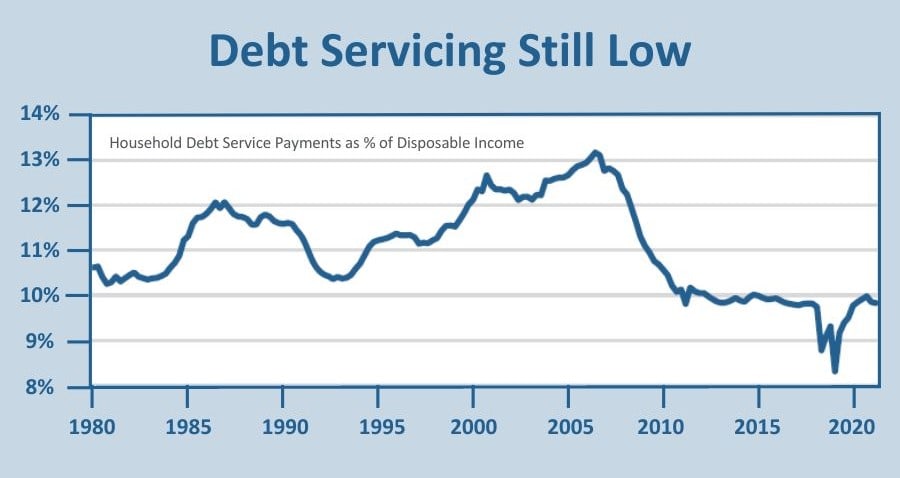

For another, the inflation that made goods and services more expensive for everyone decelerated much more quickly than wage growth this year. Indeed, for most of this year, wage gains outpaced inflation, restoring worker purchasing power; by mid-year, inflation-adjusted earnings had finally exceeded the level prevailing just before the Covid recession started. Finally, households took steps to insulate themselves from the interest rate surge by locking in the low rates prevailing before the Fed started tightening the screws. They also used a big chunk of their stimulus checks to pay down debt early in the post-pandemic recovery. Debt repayments as a percent of incomes have been rising in recent quarters but are still comfortably below historical levels.

More Oil Shocks?

But that was then. One of the key mantras about monetary policy is that it works with lags. Sometimes, the lags are short, particularly if rate changes are amplified by sudden shocks, such as an oil spike, a financial crisis, geopolitical turmoil, or other surprising event that upends public expectations. This time, the lag has been considerably longer despite the energy shocks from the war in Ukraine. The surge in oil prices in recent months has not had the usual punishing effect on activity primarily because of the ample financial resources – i.e., the aforementioned savings and hefty profits – that enabled households and businesses to absorb the increase and sustain spending. A strong job market and rising paychecks also cushioned the blow from higher energy costs.

However, these bulwarks are becoming less potent, and their ability to absorb oil price spikes and other gathering headwinds suggests that the economy will hit a rough patch in the year’s final months. Importantly, unlike the brief oil price spike last year that the administration was able to reverse by drawing on its petroleum reserves to offset supply cuts, energy prices should stay high for the foreseeable future. For one, the world’s primary producers, Saudi Arabia and Russia, are extending production cuts for the rest of the year. For another, Washington has not rebuilt its oil reserves, which could be used to offset that reduced supply, as was the case last year.

That said, while households and businesses will never welcome rising oil prices, the recent pickup has not been particularly large compared to the gyrations of the past few years. In fact, oil prices are broadly in line with where they were a year ago. By comparison, the runup over the first half of last year left oil prices on average 60% higher than a year earlier, so it would have taken a much bigger toll on activity had it not been quickly reversed over the second half. However, if the ongoing supply squeeze pushes oil prices higher, say over $100 a barrel from the current $90, on a sustained basis, the economic impact would surely increase. Not only would it constitute a tax increase for millions of motorists, but by driving up inflation, it would also prod the Federal Reserve to maintain higher interest rates.

More Hurdles Ahead

The drag from high oil prices is not the only headwind the economy faces in the coming months. The pause on student loan repayments granted during the pandemic has expired, and tens of millions of borrowers must now begin meeting their obligations, which will crimp many budgets and force spending cutbacks. Another pandemic-era source of support has expired, namely government payments to childcare providers that lowered costs for millions of parents and helped them return to the workforce. The removal is a double whammy for the economy, as it puts a dent in the labor force that is already short of workers and the wallets of parents facing higher childcare costs, most of whom are from low-income households with little savings to tide them over.

These impediments – high oil prices, student loan repayments, and more expensive childcare – are not enough to bring down the economy. Add two more shocks, however, and the drags on activity add up. One is the autoworker strike that, as of this writing, is poised to spread beyond the three auto plants initially struck and is already sending tremors through the auto industry, which is struggling to rebuild inventory on dealer lots. The crimp to production from the strike will exacerbate the shortage of vehicles and lead to higher prices, which, along with the surge in rates on auto loans, is already crimping demand.

Finally, as the calendar turns to October, the prospect of a government shutdown looms large. A short shutdown would not have much of an impact. Still, anything longer than a few weeks – which, given the rhetoric surrounding the issue, is certainly a possibility – would make a noticeable dent in activity during the fourth quarter. Beyond the direct effects of lost or delayed paychecks for millions of workers who are either furloughed or laid off in the private sector because of the shutdown, the indirect effects on the financial markets, including a possible wealth-destroying slump in stock prices, would likely result.

Heightened Recession Risk

In their last policy meeting on September 19-20, the Fed upgraded its growth outlook for both this year and next, underpinning the expectations of most officials that another rate hike is likely this year and fewer rate cuts were likely next year than thought three months ago. This more hawkish sentiment is understandable given the resilience the economy has shown so far to previous rate hikes and an inflation rate that, while receding, remains well above the Fed’s 2% target. However, policymakers may be underestimating the near-term shocks buffering the economy, which could short-circuit the economy’s momentum heading into 2024.

While the shocks alone should not cause a recession, they are unfolding just as the lags from the rate-hiking campaign are kicking in. True, households and businesses that have locked in low rates have insulated themselves from the increases over the past 18 months. But that still leaves a broad swath of consumers who need to borrow to purchase a home car or rely on credit cards for other purchases. With mortgage rates topping 7% for the first time in more than 20 years and rates on auto loans and credit cards soaring to multi-decade highs, this group of borrowers will be pulling in their horns. Meanwhile, small businesses that need to refinance expiring low-rate loans are not only facing much higher rates but are increasingly being turned away by lenders that are tightening credit standards. At this point, the Fed is more worried about sticky inflation than a recession, as it believes the former poses more of a long-run threat to the economy. It may be right, but keeping rates higher in deference to that tradeoff increases the odds of a slowdown.

If you are a Legacy client and have questions, please do not hesitate to contact your Legacy advisor. If you are not a Legacy client and are interested in learning more about our approach to personalized wealth management, please contact us at 920.967.5020 or connect@lptrust.com.

The information contained herein is for informational purposes only and does not constitute a recommendation or advice. Any opinions are those of Legacy Private Trust Company only and represent our current analysis and judgment and are subject to change. Actual results, performance, or events may differ based on changing circumstances. No statements contained herein constitute any type of guarantee, nor are they a substitute for professional legal, tax, or other specialized advice.