The economy’s roller-coaster ride continues. Last year ended with a thud, with consumers retrenching, inflation receding, and financial markets slumping. Recession fears became more pronounced, as did expectations that the Federal Reserve would soon pause its aggressive rate-hiking campaign. Fast forward to this year, and the script has been flipped. The economy appears to be racing out of the starting gate; job growth soared in January, driving unemployment down to a 53-year low; consumers regained their spending mojo, and most importantly, the inflation dragon spewed more fire.

Unsurprisingly, hopes the Fed would soon take their foot off the brake has all but vanished. Most investors had, until recently, fully expected the Fed to cut rates later this year in response to weak conditions and rising unemployment. Today, traders are pricing in more rate hikes than the Fed had forecast in December. But the financial markets are also warning of a dire outcome; with short-term rates exceeding long-term yields by the widest margin since the 1980s, this so-called inverted yield curve is signaling a recession within the foreseeable future. The implication is that the Fed’s tough anti-inflation rate hikes will go too far, sending the economy into a tailspin and leading to much lower interest rates.

We agree that a mild recession could potentially happen later this year. Still, the vigor shown in January’s jobs and retail sales reports has emboldened some to believe the Fed can restore price stability without slowing the economy. That’s possible, but such an outcome following an aggressive rate-hiking campaign and steeply inverted yield curve would defy history. More than likely, the early-year growth and inflation spike is another bump in the road that has been a common feature of this erratic post-pandemic recovery. The Fed indicates that its rate-setting decisions will depend on incoming data. In a highly volatile data environment, the central bank may embark on a risky strategy that relies on misleading information.

January’s Upside Surprises

Over most of the second half of last year, hopes were high that the Fed’s inflation-fighting strategy was bearing fruit. The most optimistic scenario the central bank hoped for was an economy that gradually slowed while inflation steadily cooled towards its 2% target. That journey seemed to be well underway. Employers stepped back from the frenzied hiring pace seen earlier in the year, consumer spending tapered off, and most importantly, inflation retreated from a peak of 9.1% in June to 6.6% in December. There was still more work to do, but the Fed predicted in December that one or two more rate hikes would do the job, marking the end of the most aggressive rate-hiking campaign since the 1980s.

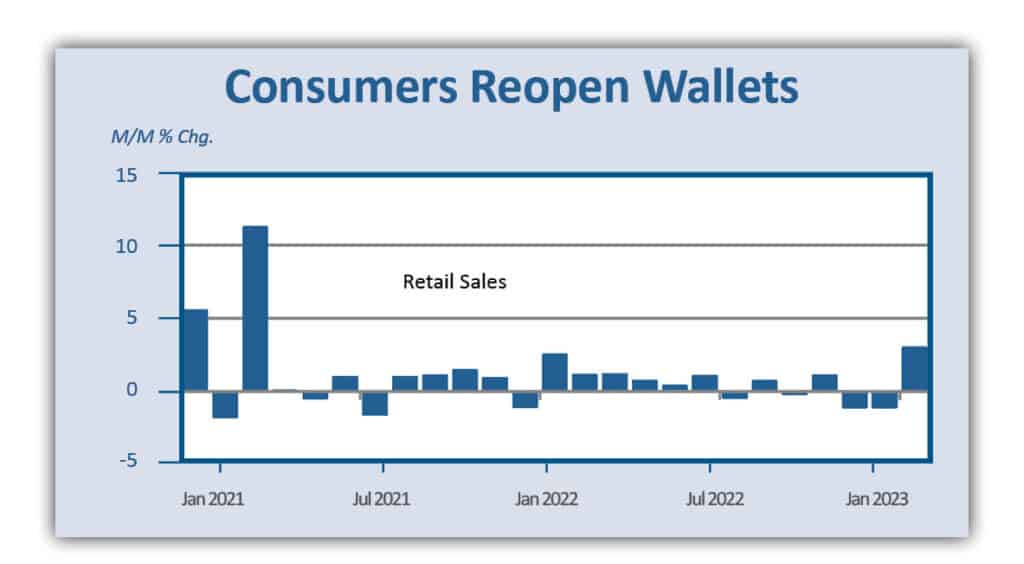

But like many well-laid plans, this one appears to be coming off the rails as the curtain rises in 2023. Job growth picked up in January, with more than half-million workers added to payrolls – the most in six months – consumers flocked back to stores after a soft holiday shopping season, spurring the strongest January gain in retail sales in nearly two years and inflation, as measured by the consumer price index, staged its most significant increase in seven months, jumping by 0.5% following a slight 0.1% increase in December.

This year, the resurgence of economic activity and inflation out of the gate has upended expectations. Investors who were skeptical of the Fed’s intentions late last year now believe they will go even further than monetary officials predicted in December, sending yields sharply higher in February. For their part, the Fed is sounding a more hawkish tone than they did at the start of the year, with several officials suggesting that future rate hikes should be larger and rates will remain higher for longer.

What’s The Fed’s Next Move?

No doubt, the slew of robust economic reports for January caught everyone, including the Federal Reserve, by surprise. Taken together, they indicate a more muscular handoff to 2023 than most imagined just a month ago. If nothing else, the notion that the economy was already in a recession when the year started, something that many commentators – and some economists – firmly believed, has been debunked. Barring a complete collapse in February and March, which is improbable absent a major external shock, the first quarter is on track to post a solid 2-4% GDP growth rate.

The next Federal Reserve rate-setting meeting is scheduled for March 21-22, when another rate increase is all but certain. The Fed’s projection in December and recent hawkish comments by Fed officials signaled that a 25 basis point hike is coming. The question remains- will it match the minor quarter-point increase triggered at the last meeting on February 1, or will the Fed step it up to a sizeable half-point increase in response to the recent resilient economic and inflation data?

There will be a few key economic and inflation data reports before the March Fed meeting takes place, including two job and consumer price reports. Should they surprise on the upside, the odds would favor a larger rate hike, and the prospect of several more increases in following meetings would be on the table. Some economists already believe that the Fed’s policy rate, now in a range of 4.50-4.75%, needs to rise above 6% at some point this year, far above the consensus expectation of around 5.50%.

Inflation Is Cooling, But Not Fast Enough

Although inflation was hotter than expected in January, we believe it will not prompt a knee-jerk reaction from the Fed. For one, the longer-term trend is still cooling, even with the month-to-month acceleration. Compared to a year ago, the consumer price index slipped to 6.4% in January from 6.5% in December, marking the 7th consecutive month of slowing annual inflation. Likewise, core CPI, which excludes volatile food and energy prices, slipped to 5.6% from 5.7%. Chair Powell stated at the last Fed meeting and in follow-up comments, “the disinflationary process is starting.” That observation continues to be valid.

Indeed, core goods prices declined in three of the past four months and are up only 1.3% over the past year. Last winter, these prices rose by close to 13%. This dramatic cooling of goods inflation reflects several forces, including the shift in consumer buying habits towards services as the post-pandemic economy continues to reopen. Additionally, the supply chain snarls that restricted the availability of goods over the past two years have almost entirely cleared up. That said, the positive contribution to lowering inflation from the goods side has probably run its course.

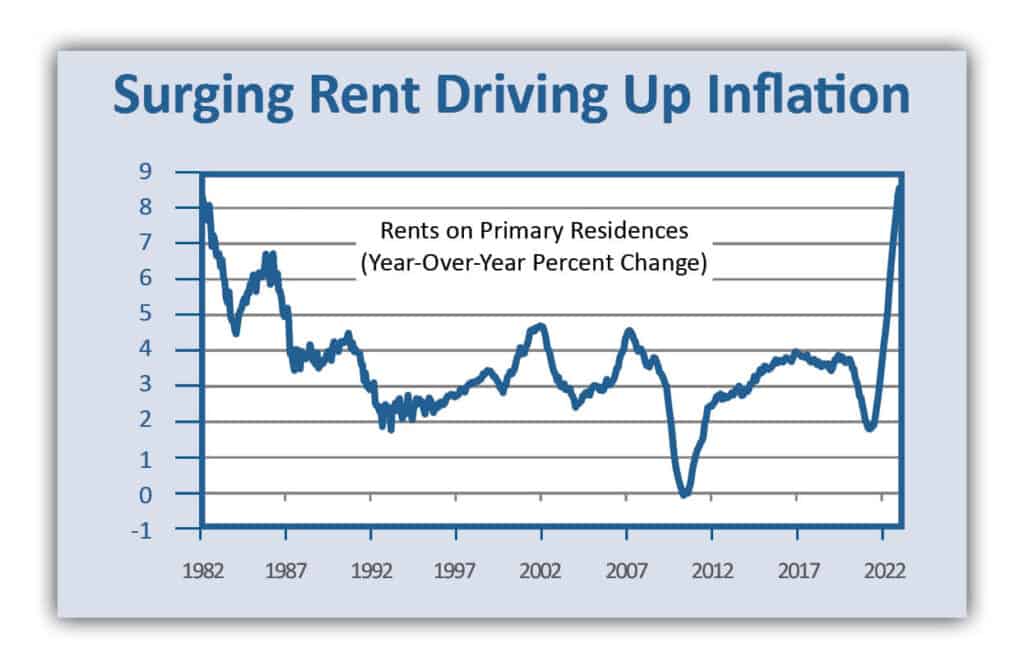

Hence, continued progress on the inflation front will depend heavily on service prices, which ran far too hot in January, up 7.2% compared to a year ago. Service prices are much stickier than prices of goods, which are influenced by global supply and demand forces that often change rapidly. Domestic conditions primarily affect service prices, particularly labor costs, which comprise the biggest expense for most service providers. A case in point is leisure and hospitality, such as restaurants, where labor shortages are particularly acute, and wages have risen faster than most private-sector workers. The largest input to service prices, shelter, continues to run hot as well, as the lagged effects of a rapid increase in home prices during Covid are still flowing through to the shelter component of CPI.

Focus On Jobs

Unsurprisingly, the Fed has been laser-focused on the labor market, convinced the inflation fight can only be won once wages cool significantly. Depending on which of the numerous measures of wages is used, labor costs are estimated to rise within a range of 4.5-6%. The Fed thinks the increases need to be slowed to about 3.5%, which, together with a 1.5% productivity trend, would be consistent with its 2% inflation target over time. The question is whether such a slowdown in wage growth can be accomplished without causing a massive increase in unemployment, which would seriously weaken workers’ bargaining power.

From our lens, such a dramatic solution is unnecessary. The current inflation upsurge has been driven mainly by Covid-related supply snarls and excess demand, fueled by pandemic-era savings, not wages. In fact, wage growth has been slowing since last fall. The increase in the Fed’s favorite labor cost measure, the Employment Cost Index, which covers both wages and benefits, slowed to 1.0% in the final quarter of 2022 from 1.2% the previous quarter. The average hourly earnings data included in the monthly employment report has also been slowing. Simply put, the dreaded wage-price spiral that keeps the Fed up at night is missing the ignition key.

The Fed is correct about the resilience in service prices and is understandably perplexed over the economy’s strong rebound in January, despite the dramatic climb in interest rates. But about 50% of the increase in the consumer price index in January was in the housing component, reflecting rising rents. The rent data, however, is not current as it includes leases negotiated over the prior twelve months. According to housing industry sources, including Zillow and Apartment List, rents are either declining or barely increasing on new leases. In the coming months, the recent trend will start to significantly influence the inflation index, pulling it down quite dramatically over the second half of the year. What’s more, the government estimates many service prices, particularly for medical care, where profit margins in the health industry are used as a proxy for doctor’s fees. Similarly, many financial service prices are based on changes in the yield curve.

The skepticism over service prices can also apply to the strength in economic data in January, which seasonal quirks can heavily influence around the turn of the year. For example, the surprising rebound in retail sales may reflect less of a post-holiday pullback than usual, as holiday sales in November and December were weak. Since the seasonal adjustment factors looked for a bigger pullback, they gave the raw data more than a typical boost in January. The risk is that the Fed become overly influenced by what could be flawed data, spurring them to raise interest rates more than necessary. As it is, the economy has yet to feel the full impact of the rate hikes already on the books, and the central bank may step harder on the brakes just when the economy is reeling from past hikes.

If you are a Legacy client and have questions, please do not hesitate to contact your Legacy advisor. If you are not a Legacy client and are interested in learning more about our approach to personalized wealth management, please contact us at 920.967.5020 or connect@lptrust.com.

The information contained herein is for informational purposes only and does not constitute a recommendation or advice. Any opinions are those of Legacy Private Trust Company only and represent our current analysis and judgment and are subject to change. Actual results, performance, or events may differ based on changing circumstances. No statements contained herein constitute any type of guarantee, nor are they a substitute for professional legal, tax, or other specialized advice.